LLMs are missing one critical thing and scientists agree (a face)

At D-ID, we believe that AI-powered digital humans will be the primary way we interact with machines in the future. No matter how clever large language models like ChatGPT, Llama, Bard or Claude are, there’s no shaking the feeling that talking to a face is better and more natural than conversing with a disembodied voice or interacting through text alone. But does science agree? We take a look at some of the academic research in this area. (Spoiler alert: yes, science does agree).

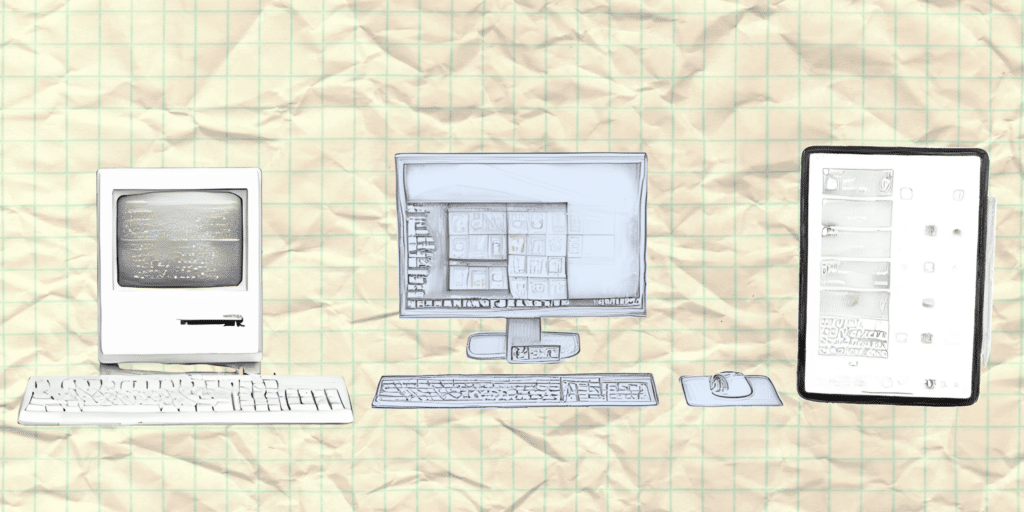

The Evolution of Interfaces

Since digital technology was born, our ability to get value from it has depended on our ability to interact with it, to command it, at will. As our tech capabilities have exploded, the interfaces we use to interact with everything around us have improved. We’ve come a long way from the green text of 1980s text-based ‘command-line interfaces’. We now have GUIs (graphical user interfaces) and the touch interface on our smartphones and tablets.

But the reality is that interacting with technology, and the businesses that use it, often remains a very frustrating experience.

We’re still forced to speak in the language of the machine – clicks, drags, scrolls, folders, navigation menus, tabs… The result is that, while the underlying capabilities of our technology have increased dramatically, these poor legacy interfaces limit our ability to leverage these increasing abilities.

More recently we have seen the explosive growth of Large Language Models like ChatGPT and Llama. Now you can ask them questions in any way you want, in an unprescribed way. They’re revolutionizing the world around us. And they feel quite human as if you’re chatting with someone. It’s even quite common for people to write ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ when they use these models, as if they were human. As NVIDIA CEO, Jensen Huang put it, “human is the new programming language”.

But the reality is that it’s not a complete person without a face. Without a face, it’s just a disembodied entity. Like some kind of ghost.

To truly connect with humans, we need interactions to be both verbal and non-verbal and humans are hard-wired to speak and interact with other human faces.

Or at least, that’s what we believe at D-ID. But does the evidence back this up? Here comes the science bit….

Brain Meets Avatar

We have previously written about how faces are better than just text or audio in this blog post. But we also wanted to understand to what extent we view human avatars differently from actual humans.

Luckily, with the rise of neuroimaging, which is a way of scientifically studying the human brain in a non-invasive manner, we can literally see the response of the brain to various stimuli. In research conducted at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, the scientists wanted to understand exactly that question, ‘if, when, and how the perception of human-like avatars and androids differs from the perception of humans’.

The team conducted a review of over 100 existing neuroimaging research papers to understand how people responded to both people and human-like avatars.

Their conclusion was simple. “Expressions of emotions in human-like avatars can be perceived similarly to human emotions, with corresponding behavioral, physiological and neuronal activations.”

In other words, “When socially interacting with humanoids, people may perceive and react as if they were interacting with human beings, showing brain activity in regions relating to emotion and interpersonal experience.”

This is backed up by an article in the Harvard Business Review led by Mike Seymour, lecturer at Sydney University, which states:

“Research from neuroscience shows that our minds are attuned to and react emotionally to facial signals. That’s why most people prefer to communicate face-to-face rather than over the telephone. In the case of digital humans, we know that what we see on the screen is an artificial construct, but we still connect instinctively to it, and we do not have to be computer experts to interpret the facial signals and make the exchange work properly.”

According to the article, one of the reasons that communication with a human-like face is better is because we are more likely to have an emotional connection.

“A humanlike face will better address emotional aspects of an interaction, such as providing reassurance or empathy.”

And we do it entirely involuntarily. A study conducted in 2022 by the School of Medicine and Psychology at The Australian National University looked for a special waveform, the ‘N170 ERP’ which appears in brain waves approximately 170 ms after a person sees a face, and is thought to reflect specialized neural processing for faces.

The team systematically reviewed literature that has investigated people’s responses to avatars versus human faces and found that “there is considerable evidence that CG faces elicit the N170 response”

Real vs. Digital

And, the more ‘real’ (or at least, photoreal) the better, according to a paper from Dr. Fred C. Miao, Professor of Marketing at University of Texas.

“Research shows that the more anthropomorphic an avatar is perceived to be, the more credible and competent it seems. The presence of an anthropomorphic appearance triggers people’s simplistic social scripts (e.g., politeness, reciprocity), which in turn induce cognitive, affective, and social responses during interactions with technology.

“Avatars with more realistic, humanlike appearance increased customers’ perceptions of social presence, leading to higher usage intentions”

There is also evidence that people don’t just relate to avatars as well as they do to people, but that in some ways avatars can be better than people.

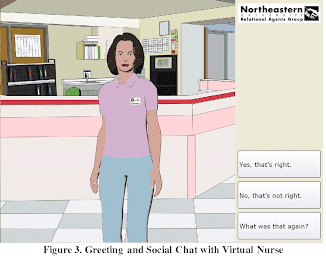

For example, a study led by Dr Timothy Bickmore, professor at Northeastern University, sought to evaluate how patients in hospital would respond to being given their discharge plan by a computer-animated conversational agent. The results were very positive:

“All patients, regardless of depressive symptoms, rated the agent very high on measures of satisfaction and ease of use, and most preferred receiving their discharge information from the agent compared to their doctors or nurses in the hospital.”

A similar study looked at the stigma among military service members that prevents them from reporting symptoms of combat-related conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). To investigate this, they researched what happened when, what they called ‘automated virtual humans’ interviewed people about their symptoms. The results were extremely positive.

“Service members reported more symptoms during a conversation with a virtual human interviewer than on the official PDHA [Post-Deployment Health Assessment]… Because respondents in both studies shared more with virtual human interviewers than an anonymized PDHA… virtual human interviewers that build rapport may provide a superior option to encourage reporting.”

Real-world Impact

In conclusion, research in neuroimaging and behavioral psychology demonstrates that we are hardwired to react emotionally and intellectually to facial signals. In fact, studies show that avatars and digital humans can evoke the same kind of emotional and neuronal responses as interactions with real humans. This serves as a compelling argument for the integration of realistic, human-like avatars in technology interfaces, not just for the sake of anthropomorphism but also for effective, empathic communication.

Such avatars, according to studies, may even surpass real human beings in certain scenarios, such as giving medical advice and mental health assessments.

These findings not only indicate the necessity of incorporating human-like avatars into digital technology and AI Video but also highlight the incredible potential for such interfaces to significantly enhance user engagement, emotional connection, and overall satisfaction.

With this emerging trend and scientific backing, we stand at the threshold of a new era—an era in which digital humans could well be the missing piece in making our interaction with technology as fluid, intuitive, and meaningful as human interaction.

Technology has caught up with our ambitions; it’s time for the interfaces to do the same.